I pace frantically while I talk raucously into the telephone outside the college newspaper office. What began as a routine phone call to find out some more information for a story ends up turning into a diatribe about how I plan to take over the Massachusetts Democratic Party and enact my politics of the impossible agenda. Thrown into the conversation at random are quick sexual jokes and other random puns leaving the person on the other end of the phone line confused and frightened.

Hanging up the phone, I walk into the Student Center lounge. I interrupt a student studying and begin a conversation. My mind races to my next thought and the next and the next.

Neurotransmitters surge.

Perhaps, you know of someone like me. I was an editor on the college paper, held internships at three major papers, a dean’s list student. I interned at a Massachusetts Senator’s re-election campaign, was active in the Women’s Center, a member of the campus philosophy society, wrote six to eight stories a week for the campus paper, and worked part-time jobs to earn extra cash.

A well-known woman around town, I was seen at every political conference or social event. I was the first one at the gym every morning exercising for one hour on the treadmill and awake far into the dawn hours scribbling poetry.

One moment, my friends would be walking with me and I would leap onto the MIT bridge and walk the railing. The next moment, I was ready to jump off into the icy waters of the Charles River.

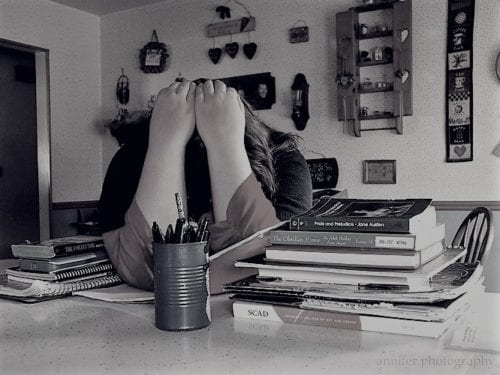

College life can be a bundle of stress to most students. However, for students like me, who have the biochemical disorder manic depression or bipolar disorder, the pressures of college may become impossible when you are dealing with mood swings, psychotic thoughts, and suicidal ideations. Imagine trying to study for a Spanish test while three or four distinct lines of thought (all unrelated) race through your mind. Now, imagine that more thoughts keep coming and coming until nothing makes sense anymore. Or try reading Shakespeare and sociology texts, when your mind has gone black.

It wasn’t easy for me to recognize that I needed help as my mood rose. It was even harder for me to ask for help. No one at the school could offer the proper intervention because no one completely understood my situation. Having gone to one session at the college counseling office intent on discussing these issues, I groped with words for a half-hour and left.

Then, one-day my mind went black in the middle of photography class. The expensive camera I was so thrilled to buy and use suddenly became too complex to operate. I lost all clarity, couldn’t think, write, or concentrate on anything.

I then went to the computer lab and posted a suicidal message to an online group. I went back to my single dorm room, locked my door, turned the music up louder, and attempted suicide.

The college RA escorted me to the emergency room after a raucous protest from me. Dressed all in black, like some Goth poster child, alone in a cubicle-sized room, I tried to convince the ER psychiatrists that I was not crazy, not even depressed, that the email I sent the group was a joke. Unfortunately, for me, I am talking millions of miles a minute, and I’m not making much sense bringing up a lot of political names and celebrities, all of whom I had worked for or met during the previous semester. Nevertheless, they sent me by ambulance to Mclean, the esteemed psychiatric hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts.

The psychiatrists at Mclean called it an acute manic depressive episode, otherwise called bipolar disorder type 1. The episodes had been re-occurring in various forms all fall semester—although, they went largely unnoticed by me as my moods fluctuated like the Atlantic off Nantucket. I spent eight days running in dark tunnels with my fellow inmates, watching another college girl break into multiple personalities, listening to tales of electroshock and a woman say she was schizophrenic and manic, which baffled me at the time (I later learned it was referred to as schizoaffective disorder). Although, the hospital recommended I spend the rest of the semester resting at home, I chose to go back to campus under the care of an off-campus therapist and psychopharmacologist. Back on campus, I spent much time recovering from the stigma of hospitalization and mental illness. Rumors abounded.

College students with mental illness must believe in themselves. They must understand that they are unique, valuable and worth the effort. They must know their legal rights as stated in the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), as well as their school’s policies. They must remain clear, calm, and persistent when advocating for themselves. I wrote my symptoms, goals, and dreams down on paper in my journal. In the journal, I taped a mood chart pulled off the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance’s web site. This journal later gave my therapist and me evidence when issues and incidents came up and the deans became involved.

There is a wonderful resource in the organization Active Minds which helps students start chapters on their campuses to educate other students about stigma and what mental illness feels like.

The content of the International Bipolar Foundation blogs is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician and never disregard professional medical advice because of something you have read in any IBPF content.