My last blog post, “My Manic Summer Take Two”, was written while I was in a psychiatric hospital for psychotic mania. Well, nothing much has changed as I am still hospitalised for that episode and am writing from hospital.

To be clear, I am not writing this while I am floridly psychotic, which would be impossible (I’m sure most with bipolar I would agree). Rather, I am writing while I’m recovering from that episode. This means I’m no longer psychotic or severely manic. I’m still in hospital because I’m a little elevated, we’re in the process of changing back onto my old medication regime, my sleep cycle needs work and there’s the risk of ‘manic misadventure.’ We’re ‘fine-tuning’ everything so I have a successful and long recovery/remission out in the community.

During my past hospitalisations, I’ve identified some ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’ when it comes to visiting (or not visiting) loved ones in hospital and I’ve put them together in a rough guide. As everyone is different, I would like to point out that this is how I like to be treated and it’s always important to gauge the patient’s individual situation when visiting them.

DON’TS

1. DON’T show up unannounced. Like with physical illnesses it can be tiring having visitors. Particularly if you’re depressed and just need time to yourself.

BUT…

2. DON’T make yourself scarce. Don’t be afraid to message or ring the patient if you can’t get to the hospital. Send cards or flowers to let them know you’re thinking of them.

Psychiatric hospitals can be intimating and visiting someone in a psychiatric hospital can be confronting, but this is not an excuse not to visit (besides psychiatric hospital aren’t scary, they’re just normal hospitals with normal patients). During my first manic episode two of my good friends hardly visited for 2 months, which really hurt. Hospital can be lonely and boring so getting visitors is always the highlight of the day. (I would like to point out that those two friends have been fabulous during this manic episode).

3. DON’T pity the patient. I don’t want pity. I want empathy and at times I want sympathy, but I don’t want anyone to pity me. Pity can feed the ruminating spiral of depressive negativity and puts a wet blanket on resilience. Yes, having bipolar can be difficult at times, but it is manageable and I normally live a rich and fulfilling life. So please, no pity parties.

4. DON’T act like the patient is a different person or what they have is contagious. This is very insulting.

5. DON’T blame the person for being in hospital. No one wants to be so unwell that they have to be in hospital. It’s no one’s fault, but the guilt of this can still be crushing.

DO’S

1. DO visit when you can; but always ask the patient if they’re up for it. Visitors are a source of support and they break up the monotony of the daily hospital routine. I love getting visitors.

2. DO send flowers and cards. Not only is it a nice gesture and brightens the room, but is normalises the experience of being in hospital as a psychiatric patient (which in this day and age there should be no divide between how psychiatric and physical patients are treated, but that’s a whole other blog topic).

3. DO ask if they need anything while in hospital like magazines, a favourite snack or if a simple job needs to be done around the house. Continue that care when they are initially out of hospital like you would for someone with a broken leg. It’s hard getting back on your feet and into your regular routine once you’ve been discharged so a little extra help is often needed. You don’t need to spend all of your time caring for the person, but little thoughtful gestures go a long way.

4. DO bring fun activities into hospital. As I said, hospital can be pretty boring. I don’t know how many hours I whittled away playing monopoly or cards with friends, or just colouring on my own. These help to pass the time. Of course, some patients may not be up to playing games, it just depends on the patient’s current situation.

5. DO validate! Never underestimate the power of validation. If someone is depressed instead of responding with pity or an upbeat (and often corny) saying, say: “that sounds really tough” or something similar. If someone is psychotic, then their psychosis is just as real to them, as to whatever is going on in your life. Don’t dismiss it because chances are that person is going to become confused, angry and hostile towards you. Listen to them and take what they have to say seriously.

6. DO treat the person the same as you would when they’re well. Your loved one is still in there and no matter how unwell they are, they will know if you’re treating them differently. When I’m psychotic, although I lose touch with reality, I still retain my intelligence and empathy and I can tell if people are treating me differently. If they are it makes you feel misunderstood, isolated, paranoid and alone.

7. DO acknowledge that we’re unwell, stay in touch and offer to help out. The biggest detriment to us when we’re unwell is silence – that we’re treated like taboo because we have a mental illness so we are left alone. Silence adds to stigma and prevents people seeking early treatment or none at all. Ask how we’re feeling like how you would ask someone who has pneumonia how they’re feeling. Ask genuine and honest questions with interest. Sometimes questions are all that’s needed for us to open up. Again, just simply talking about mental illness normalises it. We don’t want our condition to be swept under the rug it when it flares up. We want to talk about it with the people we trust.

And Finally…

8. DO treat mental illness the same as psychical illness! After all mental illness is a physical illness – it just occurs in the brain. If you treat the patient with compassion, unwavering love and support, humour (again, gauge the situation), and show genuine, non-judgmental interest in what they’re experiencing then they will feel supported and loved. And in the end, that’s what we all want when we’re unwell.

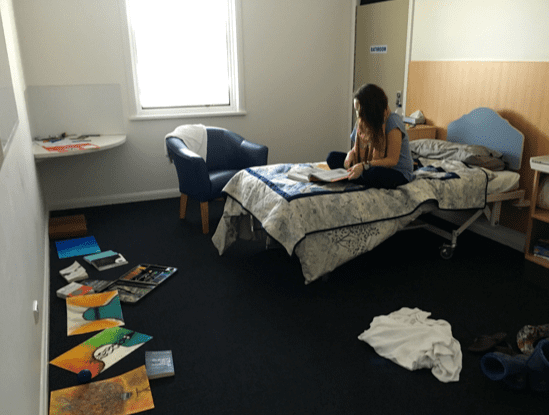

(Note: the picture is of me in my hospital room during my last current hospitalisation.)

Sally also blogs for bp Magazine and has written for Youth Today, upstart and The Change Blog. To read more of her IBPF posts, click here.